Report Summary

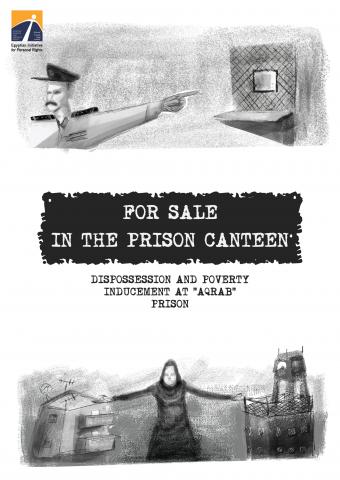

Whether in “Aqrab” or Tora Farm, Qanater or Minya prison, there is a need to investigate and address the deepening marketization of prison life: how prisoners’ most basic needs—those that the prison authorities are required to provide by law—are instead sold at exorbitant prices for the sake of the canteen’s profit. The move towards the prison-for-profit mode, by providing prisoners’ basic needs for sale in Egyptian prisons, is the thematic umbrella of this research.

This report specifically takes the case of the canteen in “Aqrab” as its focus. Bearing in mind:

(1) on the one hand, that much of the existing literature and public discourse on the medical and torture abuses at “Aqrab” does not include and unpack the prison’s economic exploitation of inmates as one of these abuses;

(2) and on the other hand, that as an exceptional facility –as a maximum-security prison—“Aqrab” is a site where several trends present in other prisons are most concentrated.

As such, this report continues to zoom in on how prisoners experience the canteen in “Aqrab” prison, as a way to understand the resonances of these practices to varying degrees across other prisons--and advocate for an end to the systematic abuses canteen and visit practices entail.

The report is structured as follows:

The first chapter gives a general background on the economic impact of the IMF loan within prisons by tracing the local and global history of prison austerity (and the marketization of prisoners’ basic needs for prison profit). It explores how the IMF loan within prison was experienced as an inflation of what were already inflated canteen prices to begin with; how this acute economic inflation was experienced by prisoners and their families; and how it is situated within the historical context of austerity measures dating back to the 80s and 90s—a time period during which services previously provided by the government- now became funded on the backs of patients, students, prisoners – for the profit of these very institutions.

The second chapter provides a general background on the history and existing violations at “Aqrab” prison. It situates the prison’s policies since its inception in 1993 within the larger trend of maximum security policies towards the beginning of the twenty-first century. The chapter proceeds to focus on violations around prisoners’ right to receive visits (and how it relates to their access to their basic needs): and includes a timeline of visit bans and violations at “Aqrab” within the past three years based on families’ testimonies and complaints to the National Council for Human Rights.

The timeline traces the violations to the present moment where a “visit registration” system has been set in place specifically at “Aqrab,” thereby precluding prisoners from their right to receive regular visits and effectively limiting visits to a prison with over 1000 inmates to 15 visits per day.

Lastly, the third chapter, deviates from existing literature on “Aqrab” by asserting that the economic exploitation taking place at the prison is also a form of the many abuses inflicted by the prison authorities; and that it amounts to the intentional poverty-inducement by the Interior Ministry against the “Aqrab” prison population. By focusing on the case of the canteen in “Aqrab” prison, the report concludes with recommendations to end economic exploitation at “Aqrab” and introduce legal safeguards to prevent the Interior ministry from carrying out similar practices of impoverishing and dispossessing inmates across other prisons.

Methods

This report is based on desktop and field research, as well as a legal review and analysis of relevant national and international legislation. Beginning as a project to investigate how the current moment of economic inflation was affecting life behind bars, the research snowballed into a focus on the canteen at “Aqrab” prison. In the process EIPR conducted 15 in-depth interviews between May and October of 2017 including:

(i) three relatives of prisoners detained at “Aqrab” at the time of writing this report

(ii) three lawyers who have visited and/or represented detainees held at “Aqrab”

(iii) four individuals who help coordinate e‘ashas at several prisons in Cairo

(iv) five relatives of current prisoners at Minya maximum Security and Damanhur General Prisons

(v) two former prisoners who were incarcerated at Qanater women’s prison and Tora Farm between June 2015-September 2016 and February to December 2016 respectively;

and lastly for historical perspective:

(vi) two former prisoners incarcerated in Liman Tora in 1975 and 1997 respectively

(vii) as well as a lawyer who provided EIPR with complaints documented by the Human Rights Center for Prisoners Support detailing complaints about food and clothing and the canteen prices inside the “Five Star Prison’ (Tora Farm Prison) in 1998 and Wadi el-Natroun in 1999 which are included in the report’s Appendix.

EIPR faced several challenges in conducting additional interviews than the aforementioned. Access to prisoners’ families, especially at “Aqrab” was exceptionally difficult due to contacted parties refusing to participate citing security concerns. This difficulty substantially drew out the timeline of the fieldwork interview periods. Another significant challenge was the lack of any publicly accessible information about canteen prices or expenditures inside the prison; the prison authorities and interior ministry do not disclose any information about the canteen’s operating budget and revenues to the public.

EIPR thus had to turn to other unofficial sources. It consulted copies of court rulings by the administrative court (the State Council) regarding cases that relatives of “Aqrab” prisoners filed against visit bans; as well as a complaint filed on behalf of the “Aqrab” Prisoner’s Network to the National Council for Human Rights in 2015.

The complaint to the council demanded that the council investigate the systematic banning of visits and collective punishment in “Aqrab” prison--especially after the canteen and cafeteria were simultaneously closed during the visit ban on June 29, 2015--and that the State Council Court orders a forensic inspection of the corpses of prisoners who died in custody. It includes the relatives’ personal archiving of “Aqrab” prison abuses from February 2014 to the summer of 2015 including visit bans, tagreedas, and canteen closures. The subsequent reports produced by the National Council for Human Rights, and commentary about them, in August 2015 and January 2016 were also consulted.

EIPR researchers referred to the administrative court rulings and “Aqrab” prisoner’s network archives in conjunction with a database provided by the Adalah Center for Rights and Freedom which archives prisoners’ complaints mentioned in 40 capital punishment court hearings records from 2014 to the present moment. The database organized the complaints into several categories including but not limited to complaints about poor food quality, canteen prices, and prisoners’ deteriorating medical conditions in custody. All of the aforementioned databases and archives are appended at the end of this report.

Lastly, this report builds on a review of the existing literature on “Aqrab” prison, including EIPR’s investigation into the visit ban at “Aqrab” that began in March 2015 via interviews with 11 relatives of “Aqrab” prisoners; as well as other rights organizations.

EIPR’s criminal justice researchers also conducted a literature review on the history of prison economies in other countries as a source of contextualization and comparison. Researchers in EIPR’s social justice and economics unit provided comments and edits for the economic analysis presented by the criminal justice researcher in the first chapter.

This research largely relies on prisoners’ testimonies and legal archives about access to food, clothing, and staples within Egyptian prisons. Complementing this research with an economic analysis of the state’s spending on prisons was not possible due to the state’s lack of transparency around its budget spending. This research could have also included an in-depth contextualization of the prison canteen within the wider economy of prisons-- especially with regards to the exploitative wages of prisoners’ labor ( for criminal prisoners who decide to work) within the prison and at outside entities like farms and welding shops. However, this report propels from the argument that the pervasiveness of the canteen within the lives of inmates across different prisons coupled with scarce documentation around its practices warrants an in-depth analysis of the canteen on its own.

Limitations

Focusing on the economy of prison canteens grew out of conversations about the current economic inflation’s impact behind bars. Prisoners’ relatives would repeatedly respond with complaints about the canteen. However, this course of the research path reveals an implicit bias in the report’s methodology: Though former prisoners or relatives interviewed relied on the canteen to widely varying degrees and budgets, none of them could not afford it altogether. Although many of the relatives interviewed recounted stories of encounters with other relatives who could not pay for canteens nor bring food during visits, the analysis from that perspective of varying economic class comes from these secondhand accounts—not primary interviews with the relatives themselves. Basing prison studies on interviews with inmates’ relatives also excludes first-hand experience of prisoners who do not have family members who try to visit them whether regularly or sporadically—which is another blind-spot for this report.

Lastly, everyone interviewed spoke of experiences of political (not criminal) imprisonment. The latter usually come from a more disadvantaged economic class, many of which opt to work in prison to support their families rather than vice versa. Thus, future studies that interrogate the experiences of economic exploitation of criminal prisoners is a necessary complement to this research.